Not their fault but the crowd’s and leaders!

Nobody should be surprised that the Capitol Riots remain a hot topic even more than three years later. It is not uncommon for investigations like the one on the January 6 mob to extend over years, even decades. Almost every week, the media reports about both the House Committee looking to establish responsibilities and courts fixing rioters on their fate.

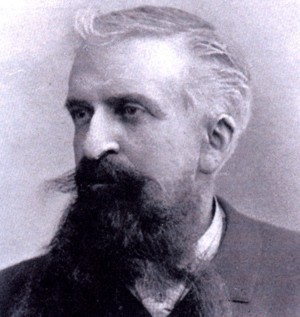

Speaking of the latter, while they attacked the capitol building as part of a mob, they have been individually facing criminal charges for not only breaking into the lawmaker’s office but also vandalizing the premises. However, the French thinker Gustave Le Bon (1841-1931), more than a century ago, performed a psychological trial in favor of them while denouncing the power of crowds and crowds’ leaders that drove those people into acting against the law and values, they believe in.

News from the last months has turned around the former president Donald Trump conviction for supposedly leading his followers to riot the capitol building and sentences having hit rioters’, most of them acknowledged their infamy. More importantly, convicted people expressed remorse for having been part of such violent actions. Some have gone further to admit having been misled.

In his book, “The crowd: A study of the popular mind (1895)”, Gustave Le Bon came to the rescue of the people taking part in the January 6 mob. According to Le Bon, the crowd changed these people’s individual and reasonable personalities into a pervertible ones which blinded their minds and pushed them to commit regrettable wrongdoings.

An irresistible power of the crowd

Yet Gustave Le Bon predicted the irresistible power of the crowd for the upcoming century (the 20th). He warned “the power of the crowd” would be “destined to absorb the other” powers as he saw it as “the only force that nothing menaces, and of which the prestige is continually on the increase (8-9).”

Not sure Le Bon was talking about only labor unions’ growing influence in companies or, even less, the universal suffrage, which pretends that the mass provides and stops governments’ power through polls.

Le Bon’s conclusions came from two landmark events in French history. The first one is the 1789 Revolution, taking place a century before his observations. The second one, the Paris Commune, happened in his time; he even was an eyewitness. Both events featured a crowd taking over the power with anarchy and terror, replacing established rules, at least for a time. History has retained mass execution, especially by guillotine, a machine used to behead people, most of them were officials and their allies.

Le Bon’s prediction of the crowds’ superpower might take a longer time to come true than he expected. The two world wars had to recontextualize both national and international politics. Governments, democracies on one side and dictatorships on the other, had a more constrained control over societies, which, itself, tended to strengthen ties vis-a-vis possible aggressions.

Moreover, the apartheid system of repression in South Africa, the Mexico’s 1968 Massacre and Tiananmen Square Massacre (China, 1989) are some proofs of such a tightness. But, with the Arab Spring of 2010s Le Bon ended up being right.

If political remodeling contributed to delaying the fulfillment of Gustave Le Bon’s prediction of crowd superpower, the reconfiguration of the mediatic landscape, with the emergence of social media during the 2000s, has been playing a significant role in increasing crowds’ power. Yet studies revealed how dramatic were Facebook, Twitter and other social platforms in spreading the revolt virus through Northern Africa and the Middle East.

Furthermore, the United Kingdom Brexit referendum and, obviously, the capitol riots were such successful even thanks to social media. The reason is that those new media imploded out of control of the invisible government, on the contrary of the conventional media, which were born and grew up to the service and needs of political and economic elites.

In other words, humanity is at a time where crowds hold a superpower no matter the circumstance which would foster events. Certainly, the elites and their allies, conventional media, try to hang on, but without a regularization on social media, crowds’ preponderance will only go increasingly towards consequences similar to the invasion of the capitol building.

The aftereffect would remain unpredictable because Le Bon noted that crowds are brutal, instinctive, tyrannical, barbarian, among other qualifiers. “Crowds are only powerful for destruction,” he wrote. “Their rule is always tantamount to a barbarian phase. (12)”

To understand Le Bon’s assertions, the United States avoided the worst on January 6, 2020. The calls for hanging Vice-president Mike Pence or Speaker Nancy Pelosi could have been met. It would be in crowds’ DNA to feel invincible, be contagious, and obey to suggestions. Likewise, Le Bon bared the crowd’s sentiment of impulsiveness, mobility, irritability, credulity, exaggeration, intolerance, dictatorialness, and conservatism. All these sentiments and characteristics contribute to setting the crowd to commit crimes.

Le Bon differentiates ordinary crowds from psychological or organized crowds. He paints the former as “a gathering of individuals of whatever nationality, profession, or sex, and the chance that may have brought them together.” The latter, which resembles the January 6’s crowd, would be “an agglomeration of individuals (which) presents new characteristics very different from those of individuals composing it.”

One of such characteristics could be the crowd’s “mental unity” that leads the people forming it to drop their conscious personality to head to the same direction. Gustave Le Bon wrote about that, “the individual forming part of a crowd acquires, solely from numerical considerations, a sentiment of an invincible power which allows that individual to yield to instincts which, had the person been alone, would have been kept under restraint.”

Furthermore, Le Bon found that by contagion the psychological crowd was hypnotic. Contagion propels crowd members to share whatever objectives whether hazardous or perilous. Le Bon noted that crowds “obey all the suggestions of the operator who has deprived” the individuals of their conscious personality, and push “these individuals (to) commit acts in utter contradiction with their character and habits.” Thus, it becomes comprehensible that convicted capitol rioters voice remorse for having been involved in such acts of destruction. But have they been misled?

Under the leader’s deceitful influence

Any attempt to answer the above question passes by the leader of the crowd and the way they deal with these psychologically conditioned people. And Gustave Le Bon’s position is final: the leader’s attitudes, actions and prestige are very impactful. The political opponents have been calling for the former president Donald Trump to be taken accountable in regard to his efforts to overturn the election’s outcomes. His own words and those from right-wing opinion leaders, such as “stop the steal”, are seen as susceptible to activate his followers’ anger against electoral institutions.

Moreover, the then U.S. president’s meeting near Capitol Hill on the day of the certification of the elected president Joe Biden and the speech he held that day would be powerful enough to push to radical actions. Critics insist on the fact Mr. Trump announced he would accompany his fanatics there.

When it comes to prestige, it was about the president, the leader of the country, and above all, an actor, a man of media, and a great storyteller. At this point, Gustave Le Bon may appear too uncompromising when he writes, “these leaders are often subtle rhetoricians, seeking only their own personal interest, and endeavoring to persuade by flattering base instincts (109).”

Gustave Le Bon found that the leaders of the crowd resorted to “affirmation, repetition and contagion” to maintain control over the people and keep them united around their will. In this sense, an affirmation as simple as “stop the steal” is susceptible to constantly be repeated and embedded itself in the people’s minds.

In the landscape of the 2016 and 2020 American elections, conventional media had been purposely diverted from social media as a channel of contagion given the former’s selective characteristics set by and for the usual elites. The ideas of affirmation, repetition and contagion have obviously made their way through the field of communication from the beginning of the last century as an arm of persuasion. Unfortunately, they are used most of the time for deceitful purposes.

Previously published by Pandora’s Box on June 6, 2022